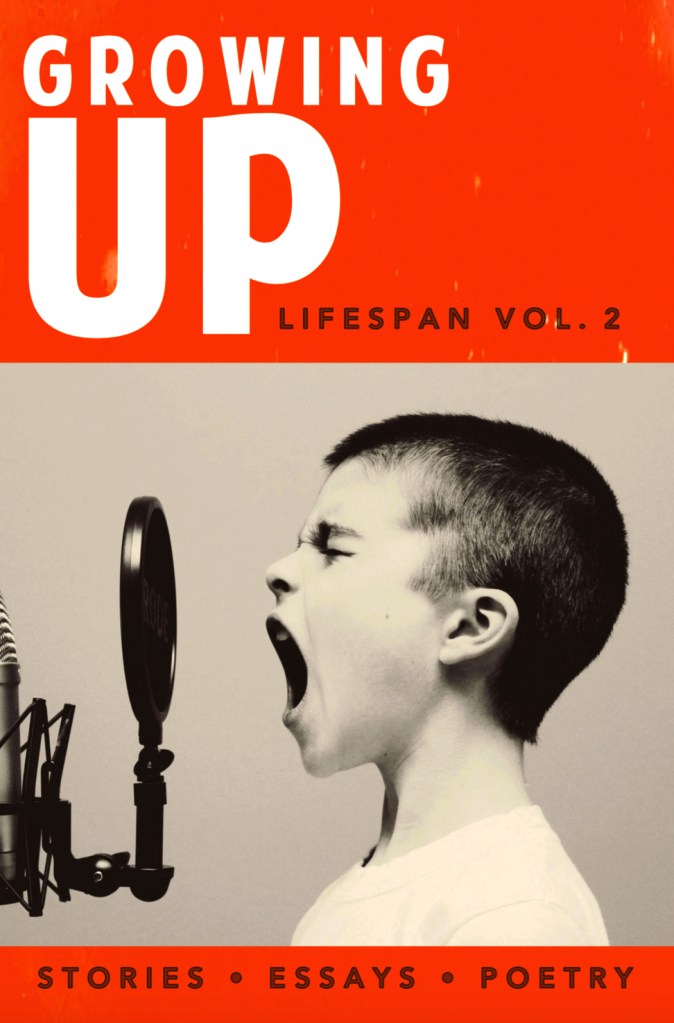

I’ve had the pleasure of working with Editor Matt Potter at PureSlush, an Australian publisher intent on celebrating the whole human lifespan in several volumes. Each of the twelve planned volumes will feature stories from a specific phase of life.

My fictional piece entitled Fire Extinguisher appears in Volume 2.

Read it here:

FIRE EXTINGUISHER

Lying in bed, Relland recited New Testament verses over and over. Passages about sin and burning. At the age of fifteen, he felt scorched, ready to ignite, as if his entire body were a page of the Bangor Daily News held too close to the woodstove.

“No relations before marriage,” repeated Pastor Martin, both from the pulpit, and every week during Youth Group meetings. “Avoid even kissing until you are engaged.”

Relland was constantly being reminded of the sins of the flesh. Either the sins themselves, or just the nature of flesh. All the animals on the family farm seemed to spend their time ooting and licking and humping and thumping. Cows were inseminated. Sows and boars made piglets. Dogs fused together in the oddest places: next to the woodpile or behind the glider on the porch. The wettest, pinkest, fleshiest parts of all the beasts were on constant display, teasing the growing boy with examples of raw, sensual energy.

Relland felt weighed down by a heat that began in his throat and singed his groin like a red-hot poker.

His options were few. In three years, presumably, he could get married. Maybe to the girl who lived on the adjacent farm. One time, he’d had a dream that he’d milked her breasts as if she were one of her family’s Holsteins. But three years was a long time to wait, and there was no guarantee that she would accept his proposal. He had barely spoken to her, although they once shared a hymnal at church.

Another option to control the burn was to see if his cousin Verna would go into the haymow again. Verna was a few years older than Relland and lived in Bangor, a city where people were often sinful, or so his mother said. Up in Aroostook, on the farms, girls did not paint their eyelids purple or Jezebel their lips.

The last time Verna visited, Relland was thirteen. That warm autumn day, Relland’s mother had suggested that he show his cousin around the place. The piglets, for instance, or the new Massey Ferguson.

Verna wasn’t interested in animals or tractors. She led Relland to the barn while their parents sat on the porch drinking lemonade and chatting. As soon as the cousins were in the haymow, Verna playfully knocked off Relland’s John Deere cap with a flick of her hand. She laughed and leaned close to him. Her hair had a funny smell, like oranges.

“It’s my shampoo,” she explained. “Citrus and Honey.”

Relland nodded. He washed his own hair with a bar of plain soap, the same soap he used to lather his hands after mucking out the barn.

It was hot. Sweat dripped down the boy’s neck. Verna casually suggested that they take off their shirts.

Relland’s eyes widened at the sight of Verna’s bra. He had only seen the industrial-looking, beige brassieres in the Montgomery Ward catalogue. Verna’s was black and as lacy as the curtains in the front room of the farm house.

Relland felt as if he were at the point of combustion, but in a few minutes they heard Uncle Vernon’s voice calling. It was time to leave.

Relland’s parents were pleased that he had entertained Verna.

“City girls are easily bored,” they said.

That night, Relland said two prayers. One for purity. Please, Lord, keep me from temptation. The other prayer was a plea for a special kind of salvation. Please, Lord, let Verna return soon, or if not Verna, please send me someone else. Some kind of fire extinguisher. Please.

It seemed more and more certain that relief would only arrive after Relland walked down the aisle of the New Life Fellowship. With someone. Anyone. And he couldn’t even do that until he was eighteen, finished with Future Farmers of America, and ready to be considered a man with a stake in the family farm. For the moment, his father treated him like a child, with constant reminders and advice and little shakes of the head.

The summer Relland turned seventeen, Uncle Vernon drove up from Bangor to help with the potato harvest. It was a bumper year and they needed extra hands. Verna came along to assist Relland’s mother in the kitchen, feeding the hired help.

Relland, himself, spent those harvest days covered in dust, picking until his fingernails turned brown. In the future, there’d be a machine harvester, but that was years away.

Relland saw Verna at meals, but there was no time to talk. At night he’d fall asleep without reciting even one Bible verse.

At the end of harvest week, Verna came upstairs to the attic room where Relland was snoring like an asthmatic dog.

“Wake up,” she whispered, sliding into his bed.

Relland didn’t stir. Verna spoke again. He lifted his head. He wasn’t sure if he were awake or dreaming. The air smelled of oranges, lemons. Verna’s shampoo.

Suddenly Verna rubbed up against his leg, like the barn cat did when she needed to be fed.

Relland felt a ring of flame encircle his torso, rise to his shoulders, “Oh God….Oh Lord, keep me pure. But….please O Lord, put out the fire,” muttered Relland out loud.

“What the hell are you babbling about?” asked Verna, laughing. “There’s no fire.”

She took charge.

In the weeks after Verna and Uncle Vernon left, Relland assumed more and more responsibility around the farm. His chores were done early, he made suggestions about how to fix the leaky corner of the potato house, and he carried himself a little taller. Even his parents noticed his calm maturity. They had prayed on it, and now it appeared that their prayers were answered.

Verna, herself, was married and divorced twice before she was twenty-five. The last Relland heard she had gotten a job out West somewhere. He never saw her again, not even at Uncle Vernon’s funeral, twenty-five years later, but he always wished her well and kept her in his prayers.

.

t

Leave a reply to Louise Ciulla Cancel reply