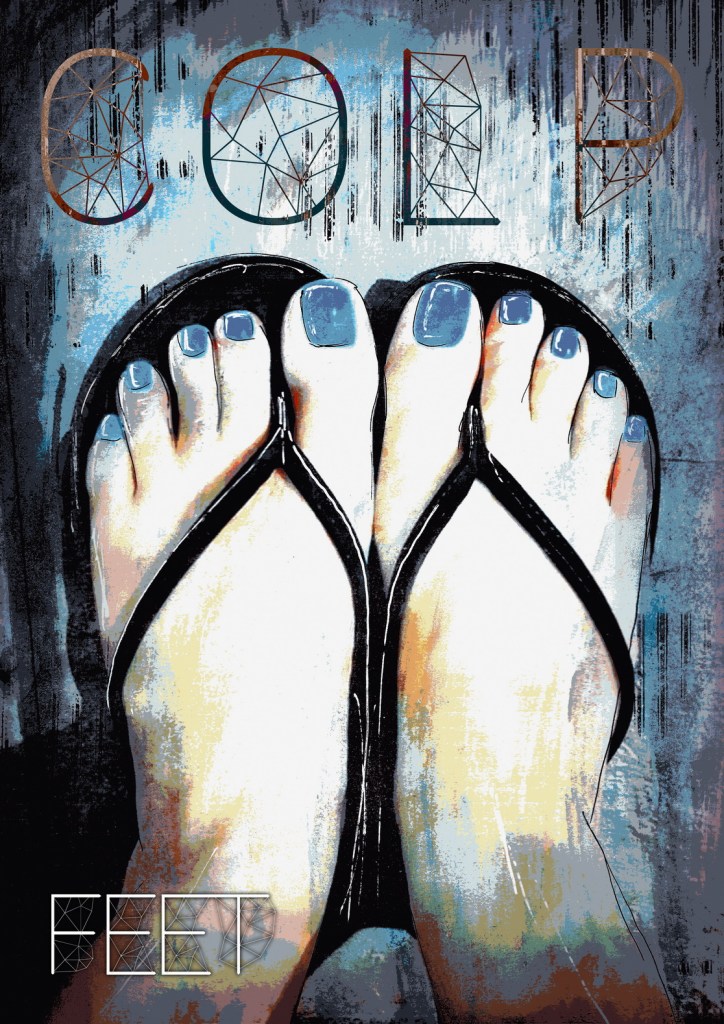

One of my short stories has found a home in COLP, a new collection from the Sydney, Australia publishing firm, Gypsum Sound.

Six Legs in Tokyo is a story of a young woman working in Japan who comes face to face with some “itchy” cross- cultural challenges.

All stories in the collection have a common thread….feet.

You can find Colp: Feet in the Kindle version or in paperback at the booksellers, or https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0B2TY7BSG

or read it here: Six Legs in Tokyo

“Sometimes I think that my mother would rather spend time with her insects than with me,” said Akiko, with a smile.

“Insects?” asked Cheryl. “Did you say insects?”

The two young colleagues were sitting in a crowded noodle shop in the middle of Tokyo, huddled over their warm bowls.

Was Akiko talking about bugs? Cheryl wasn’t sure. In two years she had been in Japan, she had made some progress with the language she’d started learning back in high school, but sometimes she doubted her comprehension. There were always surprises. Plus it was hard to hear above the noise in the shop, with the wait staff calling out orders, the cook shouting back “Hai, hai” like a soldier, and the little bell on the door jingling each time a customer came in or left.

“Is your mother a scientist?” Cheryl asked.

“No, no. She just loves our pet insects. I mean, I do too, but not in the way Okaasan does.”

Cheryl blinked. She had only known her colleague, Akiko, for a few months. She had no idea that insects played any role in Akiko’s life whatsoever. The two young women had met at the Sunshine Language School in Ikebukuro where Cheryl had taken a poorly paying job teaching American English to the occasional house-wife or salary man whose company wouldn’t pay for lessons at one of the more prestigious institutions. Akiko, herself, was part of a team of Japanese who taught their native tongue to foreign visitors. Both women were quiet, studious, and myopic. Cheryl hid her blue eyes behind the thick lenses of her tortoiseshell eyeglasses; Akiko wore wire rims. They were each in their late twenties and kept discovering things they had in common. Nerdy things, as Cheryl’s brother would have said.

On the weekend, they often met to stroll together in some of Tokyo’s parks or they went to the Yebisu Theater to catch a foreign movie. Sometimes they window-shopped, but neither one ever had occasion to wear the cute little black dresses that women their age usually wore to karaoke bars or on group dates.

Today, an ordinary Friday in early December, they were sharing a noodle dinner and talking about their families.

“What does your Mom do with insects? Does she paint them? Or study them? Or what?” asked Cheryl.

Akiko let out a sigh.

“She just dotes on them,” said the young woman.

Cheryl nodded, as if she were familiar with the idea of doting on bugs.

“Okaasan is particularly fond of our current kabutomushi, our RhinoBeetle, ” said Akiko softly.

Cheryl tried to think of a courteous way to ask if Akiko’s mother were a bit of a recluse.

“Oh goodness no, she’s a very cheerful, outgoing person,” said Akiko.

Cheryl was puzzled. She thought of her own mother, back in Massachusetts, whose only contact with insects was reaching for the canister of Raid that she kept under the kitchen sink, next to the plastic dishpan and the cleanser.

“I see,” said Cheryl, “But where do the bugs come in?”

She realized that her question could be taken in two ways. Was she asking how the bugs entered their house, or was she asking how the bugs entered their lives? She waited for her new friend to answer. But Akiko simply took another gulp of broth and said nothing. Cheryl fought her tendency to throw words into the silence. Akiko’s wire-rim glasses were fogged up from the steam rising off her noodles. She slowly took them off, and wiped them on a cotton handkerchief. Finally she spoke.

“Okaasan finds bugs very relaxing,” said Akiko.”A sort of distraction for the spirit. Especially since Father died.”

Cheryl involuntarily twitched.

“And taking care of them gives her a sense of purpose,” Akiko continued.

“I see, “said Cheryl, although she couldn’t imagine how an insect could enhance anyone’s life.

“There’s something about a bug…they’re so small, so vulnerable,’’ said Akiko.

“Uh huh,” said Cheryl.

The young American woman had never thought much about bugs. As a kid, she and her brother, Ben, would sit in the family’s summer cabin on Lake Winnipesaukee, flipping through old National Geographics, their wet swimsuits making dark circles on the canvas seats of the porch chairs. Sometimes they’d play Parcheesi and wait for a swarm of green bottle flies to tap the rutted wood table. And then BAM. They slap the invaders with a long-handled fly swatter, keeping score.

“That’s my tenth one,” Ben would say. “You’ll never catch up.”

Cheryl liked that memory, but she didn’t mention it to Akiko.

“When we moved to Tokyo, I was only eight,” continued Akiko. “ We had always lived in the country before that. We came here because Father got a job in the National Accounting Office. And at first, I couldn’t sleep. I mean, not at all. But we had brought two geji-geji with us. And that helped.”

“Geji-geji?” asked Cheryl, unsure of the word.

“Yeah, Geji-Geji“ said Akiko, making a gesture with her fingers to indicate a multiplicity of legs. “They comforted me a lot.”

“The centipedes comforted you? Really?” asked Cheryl.

“My new bedroom didn’t feel like my old bedroom. In Shikoku, the air was so clean. I could smell the sea, the citrus groves, a grove of cedar wood behind our house. But in Tokyo all I could smell was the neighbor’s cooking oil. I could tell when they were having curry rice for dinner. And the streets were so crowded. And I hated the constant sound of the trains coming and going. In any case, everything was different. But the geji-geji just went about their lives. So simple. So perfect.”

Cheryl nodded again, but the idea of insects as house pets felt creepy. She wondered if other Japanese people kept insects. Her landlady, for instance, who was always running her vacuum cleaner. She didn’t strike Cheryl as the sort to keep bugs. Nor did her boss at Sunshine Language School, a man who wore pressed white shirts, and whose bento-boxes, at lunchtime, were impeccably ordered, with each pickle sliced thin like a deck of cards. Surely someone like that wouldn’t keep a geji-geji.

During her next few outings with Akiko, Cheryl learned the names of all the insects that shared Akiko’s home. The two geji-geji were each named Lady Murasaki, although they were not the original twosome that had comforted Akiko as a child. There was also a cricket and a kuwagata or Stag beetle. But the current king of the castle was the kabutoumushi, the Rhinoceros Beetle named Ichiban. He had been raised from a grub.

Akiko and her mother were often frustrated with Ichiban because he had a tendency to escape from his cage.

“And what do you do then, when he escapes?” asked the American.

Cheryl pictured a beetle dressed in a striped prison uniform, stealthily creeping to freedom.

“We start looking, of course, in all the likely places, but Ichiban is tricky. He rarely hides in the same place twice. And you’d better believe that everything in the house stops when Ichiban is lost. Everything,” said Akiko.

“Bummer,” said Cheryl.

“Okaasan says that Ichiban has a mischievous personality. But he means no harm.”

‘You talk about this beetle as if he were a person,” said Cheryl.

“Well, he matters, you know.”

“What does that mean?” said Cheryl, thinking about all the silverfish she had come across in her damp closet and smacked with a rolled up newspaper.

“There are trillions of bugs in the world,” continued Cheryl. “How can one bug matter?”

“Because it does,” said Akiko. “You might as well ask why does one person matters.”

Cheryl thought about her brother, Ben, who had served in Afghanistan. How much she had worried about him during that time. How she printed out his emails, all his photos of the red sand, the tanks, and all his army buddies, their camo hats askew, and their arms around each other. Cheryl had been in college then. She put everything from Ben in a folder and kept it next to her bed, so she could open it up and look at it under the covers where her roommate couldn’t see. Ben mattered a lot.

“Of course one person matters,” said Cheryl, “But surely you believe that human beings are more important than insects.”

“Yes, on some level, of course. But people, animals, bugs….we’re all in this together. This existence.”

Akiko looked directly into Cheryl’s eyes when she spoke.

Soon the Christmas and New Year’s holidays approached, and Cheryl noticed that Akiko seemed less available, more distant. Cheryl hoped she hadn’t offended her friend by questioning the importance of insects. She knew she depended a bit too much on Akiko, but this Tokyo experience hadn’t really worked out as she had expected. It was hard to make friends; hard to live on her own, hard to function with only a cloudy sense of words.

The holidays were a challenge for Cheryl anyway. She realized that she was thinking more and more often about her family back in Massachusetts gathering for Christmas.

There could be snow in Worcester by now. Her grandma would be visiting, pushing her walker carefully across the frozen driveway. She pictured everyone helping to put up the Christmas tree, bringing the box of old ornaments down from the attic. Her father would swear they had more strings of lights last year. Their dog would be sniffing the pine branches and knocking off the glass balls with his tail.

At the top of the tree her mother would stick the same tired angel, the one Cheryl and Ben had when they were kids. A ragged thing made of pipe cleaners, with yellow yarn hair. One of its wings was broken, but it didn’t feel like Christmas without it.

The streets and department stores of Tokyo were beautifully lit and decorated for the winter season, but Cheryl was having trouble looking at them. Each display seemed to taunt her, remind of something missing in her life.

She had come to Tokyo, rather joyously, right out of college, at a time when her friends were going to grad school, or taking conventional jobs. She’d felt courageous, making the bold move of relocating to an unfamiliar city, looking for an adventure. She’d landed the job at Sunshine Language School, located a place to live….but then what?

Cheryl found herself dreading the end of each workday, when her students dispersed and her boss shut off the lights at Sunshine She’d head for the subway in the twilight. Several stations later, she’d emerge in the darkness, walk over to the local Conveni to buy herself a rice ball or some yellowtail for dinner, and then head home. The streets felt safe, but no one talked to her, or even exchanged a greeting.

When she’d arrive at her small rented room, she’d sit down at a table no bigger than an airline tray, and devour the rice ball. Afterwards, she’d do hand-laundry, washing out her blouse and underwear by hand, and hanging them up on the little spinning drying rack over the sink.

She had been sending a steady stream of “amazing and happy life-in-Tokyo” photos to her parents and her college friends back in the States. She didn’t even want to confide her loneliness to her brother.

One day, a few days before the New Year’s break, she asked Akiko to go to see a vintage film with her.

“I’m so sorry, Cheryl-san. I have a lot of things to do. ShoGatsu is a big deal here, you know. We clean everything for New Year’s. The food alone takes a lot of time to prepare.”

“Right,” Cheryl said, “but you really like Truffaut, don’t you? The film is The Story of Adele H. It’s a classic. You’ll love it.”

Akiko looked surprised at her insistence.

“I’m sorry, Cheryl-san. Perhaps you should ask someone else,” she said. “Like maybe a foreigner, who is not so busy.”

Cheryl nodded, knowing full well there was no one else, foreign or otherwise, whom she could ask.

The next day, Akiko sent her a text.

“Come to our house for ShoGatsu, please.”

At first Cheryl was overjoyed to receive the invitation. She had never really been invited to anyone’s home in Japan. But then she remembered the mushi. Would the centipedes be at the table? Would the Rhino Beetle be seated next to her? Her skin felt as if something were crawling on it.

But the alternative was spending the holiday sitting in her room eating cold rice balls and Face Timing with her parents.

Surely Akiko and her mother would keep the bugs in their cages during her visit. Or maybe not. She thought back to her family’s dog. He was a gangly Springer Spaniel who liked to leap up on guests and lick their faces. It never occurred to Cheryl’s parents to lock him in the basement when guests came. He was part of the family. They’d apologize for him, of course.

“Sorry, he just gets so excited.”

Cheryl and her family assumed everyone else could see how special their dog was. No doubt some of their guests hated dogs. Cheryl remembered that some people would rush off to the bathroom to wash their hands after the spaniel had coated their palms with saliva like varnish, or they’d pick dog hairs off their pants with a look of disgust.

It might be exactly the same with folks who kept mushi, thought Cheryl with repulsion. They might let their little beasts crawl over people’s arms, for instance. Or up their skirts. She wasn’t sure she could deal with it. She went back and forth with her decision. Finally, she bought a bottle of sake as a gift and got on the Keio Line. Akiko said she would meet her at Fuchu station and walk her to the house. Underneath her bulky winter coat, Cheryl felt itchy, as if the lining were made of fiberglass.

“Okaasan spent the last week cooking, “ said Akiko. “She’s so happy that she is finally getting to meet you.”

Cheryl waited for her to say that Ichiban and the other insects were happy too. But she didn’t.

The two women followed the maze of winding streets through Akiko’s neighborhood. Amber light glowed in the windows of the compact, two-story house with a flat roof.

“Here we are, Tadaima, “ said Akiko, calling out the traditional return greeting as she crossed the threshold.

Cheryl’s skin felt almost unbearably prickly. She knew that there were only five pet bugs in the house, but somehow she expected swarms of creepy-crawlies to be hovering over the delicate scrolls that hung in the alcove.

The foyer was immaculate. Nothing slithered up the walls.

Akiko’s mother came rushing to greet the visitor.

“I’m delighted to meet you,Cheryl-San, ” she said. “Please call me Susume.”

She was a young-looking fifty-five year old woman. With her tunic and her tights, she looked fashionable, way more fashionable than her daughter, but with the same wire-rim glasses. Susume helped Cheryl off with her bulky parka and the young American removed her shoes and put on guest slippers.

They sat down almost immediately around a kotatsu heater. Akiko’s mother brought out traditional dishes. Black soybeans. Sweet potato with chestnut. Burdock root. Other dishes which Cheryl didn’t recognize. At first Cheryl found herself trying surreptitiously to inspect each plate. The small bowls were black ovals, all of them shiny and well-crafted. But perhaps there was a beetle lurking somewhere underneath them. She took the stylish chopsticks off of their lacquer holder and examined them carefully. But nothing moved or wiggled, so Cheryl ate heartily, remembering to compliment Susume-san at regular intervals.

Akiko’s mother looked pleased. The conversation flowed. Susume happily reminisced about her childhood.

“I lived out in the countryside. Shikoku had no bridges to other islands, when I was a girl. Of course it does now. My father was a farmer. Beautiful country. We grew grapefruits. I remember how sweet they were, the feeling of the sticky juice on my chin. I can still recall the sounds on a summer night. The frogs, the cicadas.”

She poured some more sake into each cup and smiled at Cheryl.

“Sometimes we find happiness in the smallest things, don’t we?”

Later that evening, Cheryl went to use the washroom. Akiko led the way. They walked by a low table on which there were several large terrariums.

“Here’s the rest of the family,” said Akiko.

She pointed out the centipedes who were huddled at opposite ends of the glass cage like two cautious roommates. Cheryl looked briefly at the cricket and the kuwagata beetle. Finally, in the largest terrarium was the prized Rhinoceros beetle, Ichiban, himself.

“Oh,” said Cheryl, not knowing what to say.

“You have to get down at his level,” said Akiko. “And look carefully at his face.”

Cheryl knelt down stiffly, as if she had dropped a small coin on a dirty sidewalk and was loathed to pick it up. She peered into the glass cage. She wasn’t sure where to even find the insect’s face. She looked at the creature for a minute and then stood up again.

Akiko stayed kneeling, talking in a soft voice to the beetle, before returning to the living room.

After using the bathroom, Cheryl had to pass by the terrariums again. The hallway was empty. She remembered what Akiko said, about getting down on their level. That was the key to understanding them. Maybe she should try it. She crouched down slowly and peered into the cages. The cricket, the beetle and the centipedes weren’t moving much, but the Rhinoceros beetle was hanging on a branch cutting. Just hanging there, like an ornament on a Christmas tree. Ichiban was about as long as a small breakfast sausage, with a shiny brown carapace. His body looked smooth.

Noiselessly, Akiko’s mother came padding into the hallway in her slippers. She knelt down gracefully next to Cheryl and began pointing out Ichiban’s features.

“See how his mandibles curve, like a dancer’s arms?” said Susume.

Cheryl nodded, although she wasn’t sure exactly what the words meant. Which part was mandible, what was leg, what was antenna? She squinted into the glass.

“Oh let’s get him out and you can take a closer look,” said Cheryl’s host. “I have to change his bedding anyway.”

Cheryl recoiled a bit.

“Will he bite?” she asked.

“Oh, no,” said Akiko’s mother. “Perfectly harmless. That’s why children love them.”

Susume reached in and let Ichiban crawl onto her open palm.

“Good boy. He didn’t hiss.”

“Hiss?” asked Cheryl. “He can hiss?”

“Yes, he rubs his tummy with his wings, like so many insects do. But he just does that when he’s disturbed.”

Akiko’s mother held Ichiban up close to Cheryl’s eyes so the near-sighted girl could get a better look. She carefully pointed out the tiny spikes on the six legs.

“So he can grip as he climbs,” she explained. “And he loves to climb.”

Cheryl listened as Susume talked about raising Ichiban. How she had gotten a baby grub at a pet store in the spring, how the tiny thing had unfolded and pulsed. She talked about watching the larva turn into a pupa.

“This is his final stage. He will probably only live as a beetle for another year,” said Akiko’s mother.

Cheryl wondered if Akiko would bury Ichiban someplace when he died, but she didn’t feel comfortable asking.

“But he will have had a good life,” she added. “I give him fruit jelly as much as he wants.”

Cheryl stared a little longer at Ichiban, nestled peacefully in Susume’s hand. She tried to imagine his tiny brain inside his tiny head.

“He has a brain, doesn’t he?” she asked.

“Mochiron, of course,” said Akiko’s mother.

Cheryl wondered what a beetle’s brain could possibly be like, what primitive processes occurred inside it? And yet, could one ever really know how someone else’s brain worked? She thought about the time her brother came home, fatigued and changed from his tour of duty in Afghanistan. She’d stare at his closely-shaven face, his high forehead. What had he seen? What images was he holding onto, what memories were lodged in his mind?

Cheryl looked back at Ichiban. It struck her suddenly that every creature, no matter how small or large, just inhabits its own secret world.

Both Cheryl and Akiko’s mother were silent for a few minutes, watching Ichiban climb up a potted vine.

“You know, it’s hard to live as we humans do now. So much concrete,” said Akiko’s mother finally. “The noise, and the congestion, and the rushing about. But then there’s Ichiban. To remind us of something else.”

Cheryl looked once again at the beetle. Squinting, she could see the small spikes at the end of his antenna as delicate as a thorn on a rose bush.

“Would you like to hold him?” asked Akiko’s mother, not really waiting for an answer.

Cheryl was surprised to find herself at ease when Susume placed Ichiban on her moist palm. His gait felt like a tickle. Cheryl touched the chocolate colored carapace with her other hand.

After a few minutes, Akiko’s mother suggested that they return Ichiban to his cage.

“He’s probably had enough of all this attention,” she said.

They went back into the living room to join Akiko, who had already cleared the dishes and set out more tea and a bowl of fruit. The three of them huddled around the warm kotatsu and ate persimmons, pulpy and sweet. They talked for several hours.

“Please visit us often from now on,” said Akiko’s mother as Cheryl was leaving.

On the subway ride home, Cheryl began to wonder what else besides insects she had never looked at closely. What other living things had she been ignoring? Thousands of them, probably. There were so many ways of being alive in the world. Here in Japan. Back home in Massachusetts. All over the planet.

She leaned her head against the back of her seat and let herself be gently rocked by the speeding train. She was full of good food and slightly sleepy. Outside the window, the loud and artificial Tokyo night flashed by in a burst of pink and green and red. She stared at the fireworks blooming like flowers in the sky. It was the first day of a new year.

FINIS

I

P.S. Local folks…..do come to Poetry for a Midsummer’s Night which I am hosting as North Haven Poet Laureate. The event will be held at 6:30 outdoors in the Reading Garden of the Memorial Library on June 23rd, Thursday. Listen or read your own work. Register in advance. Thank you!

Leave a comment